|

August 21, 2020 Set 1

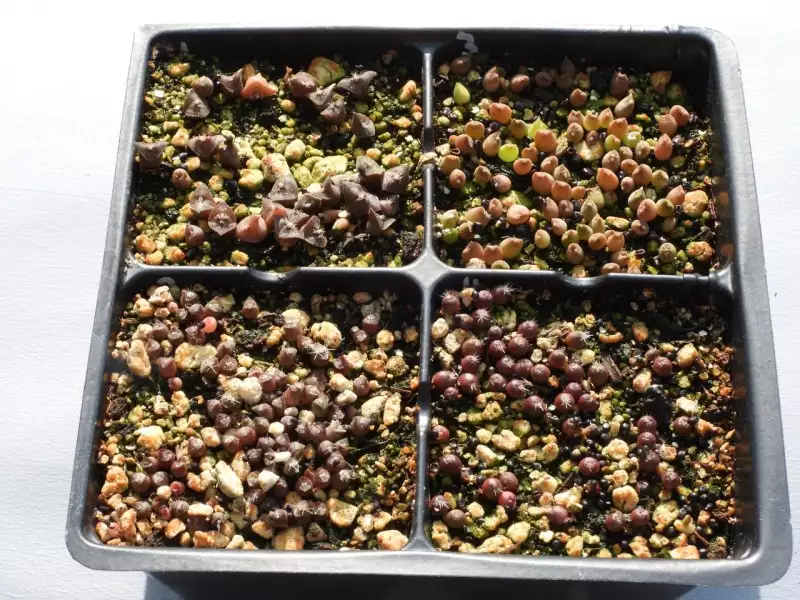

Top left: Peniocereus greggii SNL1 (50) max germination count = 32 Count Sept 19 = 33 Top right: Astrophytum capricorne (100) max germination count = 78 Count Sept 19 = 76

Bottom left: Echinocereus triglochidiatus (150) max germination count = 70 Count Sept 19 = 86 Bottom right: Escobaria missouriensis SNL155 (150) max germination count = 48 Count Sept 19 = 45

I counted the number of germinations starting the day of the first germinations (3 to 6 days after sowing) to around ten to 14 days after the first germination. This was the day of the maximum germination count. It's not exact; it's just based on my experience with cactus seed germination. As you can see comparing the September 19 count to the maximum germination count, some additional germination occurred, and some loss happened by September 19. I've also included the number of seeds that I've sown in all the tables of counts, so you can easily get an idea of germination success. Most of us cactus seed nuts consider anything above 50% gratifying, and our occasional successes above 75% truly amazing. For my show-and-tell, I did choose seeds that I've had consistent good luck with. There are some cactus species that I've had exactly 0% germination every time I tried them over many years. I have no idea why. Note that in a perfect world, the September 19 seedling count would be identical for each of the 8 cells of seedlings. As you'll see, the world is very imperfect.

These are the youngest plants about two weeks after germination. These look the most uniform within their population. There isn't much evolutionary pressure for young seedlings to look different . Note the Echinocereus triglochidiatus (bottom left) and the Esccobaria missouriensis (bottom right). They look very different at this early stage; the Escobarias are quite round, and the Echinocereus are more angular. You can see the tiny cotyledons of the Echinocereus triglochidiatus (the pointy things by the emerging spines), but these are very hard to make out on the Escobaria missouriensis. (They're there!) The small number and size of the spines don't obscure the colors of the plant skins. If you're wondering why the plants are reddish brown and not green, its because they are getting so much light from the LEDs (a good thing!) that the other colored pigments (carotenes, xanthophylls, etc) overpower the green of the chlorophyll. This effect is least seen in the Astrophytim capricorne; eventually, of course, these several green individuals will also take on the same pale buffy brown as their mates. It turns out that newly germinated cacti don't generally want strong sunlight. In fact, they are usually killed by direct sun. In nature, cactus seeds usually germinate in light-protected spots, like under trees, or bushes, or in the shade of rocks. We're lucky these past 100 years or so that the available 4' fluorescent bulbs close to the seeds approximates this necessary shaded environment. Modernly, 4' LEDs are even better. They give a similar light quality to fluorescents with very very much less useless heat. I grew the seedlings you've been examining about 3" from the LED tubes. This same distance from a fluorescent tube would not be good for the plants. Growing under fluorescents would always give you etiolated (stringy skinny) seedlings because you had to stay about 8" away from the lights to avoid maybe cooking the seedlings. But the light is less intense the farther away you are from the light source (inverse square law), so the etiolation results. But, if you get the seedlings to better light as soon as they really need it, the etiolation is grown out of and the seedling looks normal after a while. The reason no biggish cactus looks as red as these seedlings is at some point in their growth they need much more intense light. This intense light makes so much green chlorophyll that the other colors are swamped out. The more intense light is obtained in nature by the plant getting taller as it grows. Whatever was shading the plant no longer does so, or not as much.

(Another aside: The 4' LED fixtures plus bulbs are now comparable in cost to fluorescents ($30 per two-tube fixture plus two bulbs at Costco). One annoying thing about fluorescents besides the heat is that they actually lose about half their light intensity in a couple of year's use. I routinely gave my fluorescent bulbs to the local Goodwill after two years. The bulbs were still good as just a miscellaneous light source. LEDs are supposed to stay bright, going down to 70% of their brightness over 50,000 hours, which is about 25 year's worth of cactus growing. One more thing - LEDs in my possession have not hummed like all fluorescents do after a while.)

(The reason many house-grown cacti don't quite look right is that they don't get the light intensity they need inside the usual house. They are always growing toward any light source and thereby appear "stretched." That is, spacing between areoles is too big for that species when grown in adequate light . The skin color of the grown-in-house plant tends to be pale green, the sign of not enough intense light. Lots of people are fooled by the bright light that washes into their houses through south-facing windows. They don't realize the the human eye adjusts to various light intensities very rapidly. Our eyes function over ten powers of ten. That is our eyes can work in relative intensity 1, all the way out to relative intensity 10,000,000,000. This is partly what your iris does for you. Sunlight coming through a window, even a south window, drops off in intensity very rapidly. A cactus a couple of feet in your house will slowly starve to death, unless it's one of the jungle cacti.)

A few years ago I was in Saguaro Cactus National Park, the piece west of Tucson. I ran across a small saguaro, about 8 in tall, that was brick red. It was in the open, in full sun. I wondered how it came to be there. It should be dead. The natural history of saguaros is that a bird eats some saguaro seeds and sits in a tree to digest its meal and excretes some of the undigested seeds. The saguaro seed is now in a shady environment under a tree and can easily germinate when rains come. There is birdshit fertilizer, even. There are some trees that are favorite perching spots of saguaro seed-eating birds, because you can find these trees with maybe ten to dozens of saguaros of various sizes growing in their shade. The bush or tree with all these saguaros is termed a "nurse plant." Over many years, usually one of these many saguaros out-competes the others for food and water. The losers die, starved to death. The surviving saguaro keeps on growing up through the tree branches and eventually gets above the branches, in full sun. It may be 5 or 10 feet tall, maybe more, at this point. It now is tolerant of the full sunlight and gets the benefit of having available more of the sun's energy than when it was shaded by the tree and it now grows like crazy (for a saguaro). You can see this relationship all over the saguaro habitat. You'll find many saguaros about ten feet tall growing up through a tree canopy. Eventually, because the saguaro's root system gets really huge and is super good at picking up water and food, the nurse tree is killed by starvation, kind of like the other saguaros that were also there at first. The nurse tree rots away over time, the termites eat it, etc. The saguaro stands there, silent, with eventually no evidence of the nurse tree ever having existed. Kind of a crummy thanks for nurturing that saguaro for so long.

This is the reason for my surprise at that small brick red saguaro out in the open. It's not supposed to happen. But, every new life is nature's experiment testing the possibility of tweaking some improvement in existing life or making new life forms. Somehow that little guy made it to 8" tall in the most hostile environment possible for a newly germinating and growing saguaro. Of course, maybe some tourist decided to steal a small saguaro, thought better of it, and in his ignorance decided to get rid of the evidence by planting the thing back into the ground, in the wrong place. This is the more likely story.